FORT MADISON – Betsy Ross is one of the most cherished figures of American History and, she had connections to Lee County.

Ross’ daughter, Clarissa Sidney Claypoole Wilson, and her granddaughters, Rachel Wilson Albright and twins Sophia Wilson Hildebrandt and Elizabeth Wilson Campion were connected to a family named Albright in Fort Madison.

Rachel Albright was the wife of Jacob W. Albright.

The Albright (Betsy Ross) House is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and still stands at 716-718 Ave. F in Fort Madison.

The Italianate-style home was built by the Albright brothers in 1858 and was placed on the register in 1978.

For more than two centuries, Americans have saluted Old Glory in times of trial and triumph. Over farmlands and town squares, atop skyscrapers and capitol buildings, the American flag soars. It reminds us of our history – 13 colonies that rose up against an empire – and celebrates the spirit of 50 proud states that form our Union today. On Flag Day and during National Flag Week, we pay tribute to the banner that weaves us together and waves above us all. Betsy Griscom Ross is credited with constructing the first U.S. flag.

Betsy’s story

Elizabeth Griscom was born Jan. 1, 1752, in the bustling colonial city of Philadelphia. She was the eighth of 17 children. Her parents, Rebecca James Griscom and Samuel Griscom, were Quakers. The daughter of generations of craftsman (her father was a house carpenter), young Betsy attended a Quaker school and was then apprenticed to William Webster, an upholsterer. In Webster’s workshop she learned to sew mattresses, chair covers and window blinds.

In 1773, at age 21, Betsy crossed the river to New Jersey to elope with John Ross, a fellow apprentice of Webster’s and the son of an Episcopal rector – a double act of defiance that got her expelled from the Quaker church. The Rosses started their own upholstery shop, and John joined the militia. He died after barely two years of marriage. Though family legend would attribute John’s death to a gunpowder explosion, illness is a more likely culprit.

In the summer of 1776 (or possibly 1777) Betsy, newly widowed, is said to have received a visit from Gen. George Washington regarding a design for a flag for the new nation. Washington and the Continental Congress had come up with the basic layout, but, according to legend, Betsy allegedly finalized the design, arguing for stars with five points (Washington had suggested six) because the cloth could be folded and cut out with a single snip.

The tale of Washington’s visit to Ross was first made public in 1870, nearly a century later, by Betsy’s grandson. However, the flag’s design was not fixed until later than 1776 or 1777. Charles Wilson Peale’s 1779 painting of George Washington following the 1777 Battle of Princeton features a flag with six-pointed stars.

Betsy Ross was making flags around that time – a receipt shows that the Pennsylvania State Navy Board paid her 15 pounds for sewing ship’s standards. But similar receipts exist for Philadelphia seamstresses Margaret Manning (from as early as 1775), Cornelia Bridges (1776) and Rebecca Young, whose daughter Mary Pickersgill would sew the mammoth flag that later inspired Francis Scott Key to write “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Widowed again

In June 1777, Betsy married Joseph Ashburn, a sailor, with whom she had two daughters. In 1782 Ashburn was apprehended while working as a privateer in the West Indies and died in a British prison. A year later, Betsy married John Claypoole, a man who had grown up with her in Philadelphia’s Quaker community and had been imprisoned in England with Ashburn. A few months after their wedding, the Treaty of Paris was signed, ending the Revolutionary War. The couple had five daughters.

Over the next decades, Betsy Claypoole and her daughters sewed upholstery and made flags, banners and standards for the new nation. In 1810 she made six 18-by-24-foot garrison flags to be sent to New Orleans. The next year she made 27 flags for the Indian Department.

Ross’ Final days

Ross spent her last decade in quiet retirement, her vision failing, and died in 1836, at age 84.

Her body was first buried at the Free Quaker burial ground on North Fifth Street in Philadelphia. Twenty years later, her remains were exhumed and reburied in Mount Moriah Cemetery in the Cobbs Creek Park section of Philadelphia. In preparation for the U.S. Bicentennial, the city ordered the remains moved to the courtyard of the Betsy Ross House in 1975. However, workers found no remains under her tombstone. Bones found elsewhere in the family plot were deemed to be hers and were re-interred in the current grave visited by tourists at the Betsy Ross House.

In Fort Madison

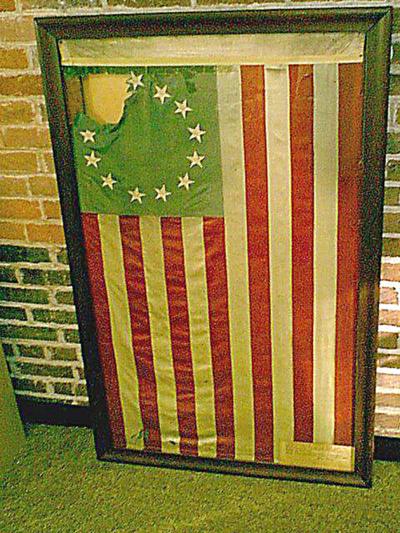

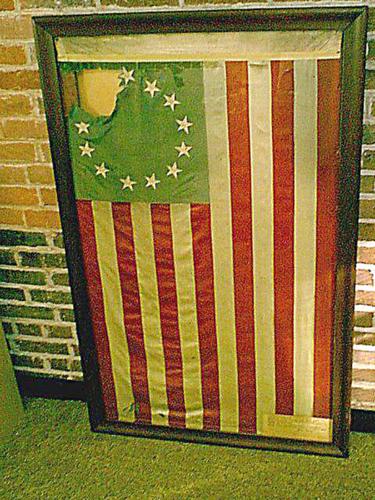

When Rachel Wilson Albright was a child in Philadelphia, she helped her grandmother Betsy sew flags, and later duplicated the design of the original “circle-of-13 stars” flag as small replicas for sale and for special occasions. Sometime between 1858 and 1864, Betsy’s daughter and Rachel’s mother, Clarissa Wilson, came from Philadelphia to live with the Albrights.

In 1905, at almost 93 years old, Rachel sewed her final replica flag and donated it to St. Luke’s Episcopal Church at 6th St. and Ave. E, Fort Madison. Signed and dated by Rachel Wilson Albright, the flag remains there on display, preserved under glass.

Along with many other members of the Albright family, Rachel, her mother and her twin sisters Sophia Wilson Hildebrandt and Elizabeth Wilson Campion, are buried in Fort Madison’s City Cemetery. Clarissa died July 19, 1864. Elizabeth died Oct. 29, 1900. Sophia died May 8, 1891. Rachel died April 18, 1905.

In the cemetery is a large granite marker set by the Jean Espy chapter of the Daughters of the Revolution commemorating the fact that Ross’ daughter and the granddaughters are buried there.

Albright House

Rachel’s husband Jacob W. Albright and William G. Albright form Reading, Pa., were partners in the Albright Dry Goods and Notions store at 719 Avenue G for more than 50 years.

In 1857, the brothers commissioned Marr & Creps to build the three-story brick Italianate duplex as their families’ home. W. Albright and family lived on the left side, and J.W. Albright and family lived on the right side.

The house is three stories tall with ceiling heights of 12 feet for the first two floors and seven feet for the third floor. The third floor likely contained bedrooms for the children. Each residence consisted of 13 rooms and both homes were mirror images.

Patterned after a high-style design of noted Philadelphia architect, Samuel Sloan, the house was completed in 1858 for a reported cost of $14,000, according to the abstract. At that time, the size and grandeur of the home were reported to rival the governor’s mansion.

The building is constructed of unfired brick (the walls are three courses thick) on a sandstone foundation. Missing now, but scheduled to be reapplied when refurbished, are 76 ornate cornice brackets arranged in pairs beneath the massive eaves at the roofline. The total space of the entire building exceeds 9,000 square feet.

Today, the floor plan of the east side residence remains very close to that of the original design.

Cooking was originally done in a basement kitchen, and food was transported up to the butler’s pantry on the first floor via a dumb waiter. The food was then “plated” and served in the formal dining room. There is a somewhat hidden service staircase that leads from the rear of the butler’s pantry up to a bedroom on the second floor that was probably a servant’s or nanny’s quarters.

Originally, two brick stables stood behind the house, and today there are still remnants of a herringbone-patterned brick courtyard that once joined the house and stables.

Information for this article was taken in part from History.com, Fort Madison Area Convention & Visitors Bureau “Fort Madison” brochure and other sources.